Social media has given its users the gift of globalization and lightning-speed communication. Unfortunately, this newfound tool brings the curses of bias and misinformation. We’ve dug deeper into social media’s effects through primary and secondary evidence. As with anything, social media has positive and negative outcomes over political participation.

Professor Soobun Lee of Incheon National University and Dr. Cheonsoo Kim of Myongji University pointed out revolutionary aspects of social media in their 2021 article, “Does social media type matter to politics?” They add that not only does the internet make it widely accessible for people to seek out political information, but it also teaches users the civic skills necessary to participate in politics actively.

While it’s difficult to say if these perks outweigh the dangerous power of disinformation online, it’s a face of social media activism to appreciate. As expected, the research points fingers at social media for effectively spreading misinformation, but not all platforms are created equal.

Here at Biasly, we conducted research to find out users’ firsthand social media experiences online and how they are affecting people’s political opinions and news consumption. We used a short survey to gauge the participants’ political activity concerning their off-the-clock social media usage.

Social Media in an Era of Polarization

We conducted research through Google Forms and distributed it to political analysts and journalists by email. In the survey, participants answered six mandatory questions regarding their social media and news consumption habits and five optional demographic questions.

The survey was confidential regardless of how they answered the demographic segment, as they wouldn’t identify them in any way. The mandatory section asked participants how much time they spent on social media, what platforms they used, what hashtags frequently came up, and what politically affiliated news outlets they interacted with online. As for demographic information, We asked about participants’ political affiliation, race, gender identity, sexual orientation, and age group.

Even though the survey suffered from a small sample size, an advantage we had was having access to a broader range of platform users as opposed to researchers like Dr. Ro’ee Levy of Tel Aviv University, who chose to narrow his focus on Facebook users. His research in the paper “Social Media, News Consumption, and Polarization: Evidence From a Field Experiment” explores Facebook’s effect on users’ political activity on and offline.

Besides Dr. Levy’s extensive field experiment regarding Facebook’s effects on polarization and news consumption from social media, Italian economist Stefano DellaVigna and associate professor Ethan Kaplan from UC Berkley thoroughly explained the results of limited access to varied viewpoints. Their article discusses the relationship between voter turnout and the consumption of polarized news in the United States.

The combination of these experiments provides the primary research survey with the necessary background it needs to be able to stand on its own as valid data.

Social Media and News Consumption and How They Are Related

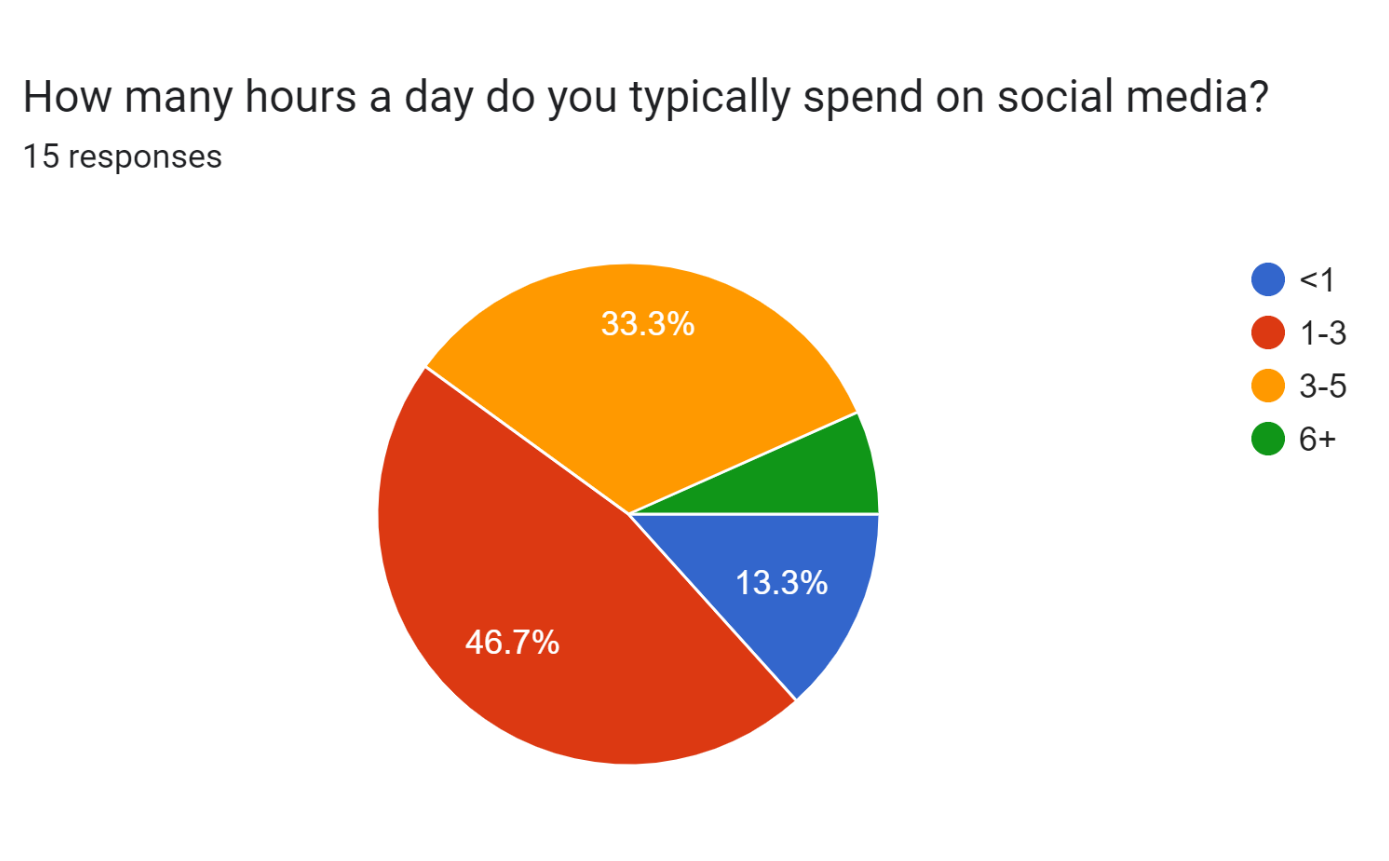

Even without the demographic and historical context, the survey’s results varied greatly between each participant regardless of the small scale of the experiment. Seven participants reported spending one to three hours on social media daily. Out of the other half of the group, five people indicated three to five hours, two reported less than one hour, and one indicated over six hours of social media activity daily.

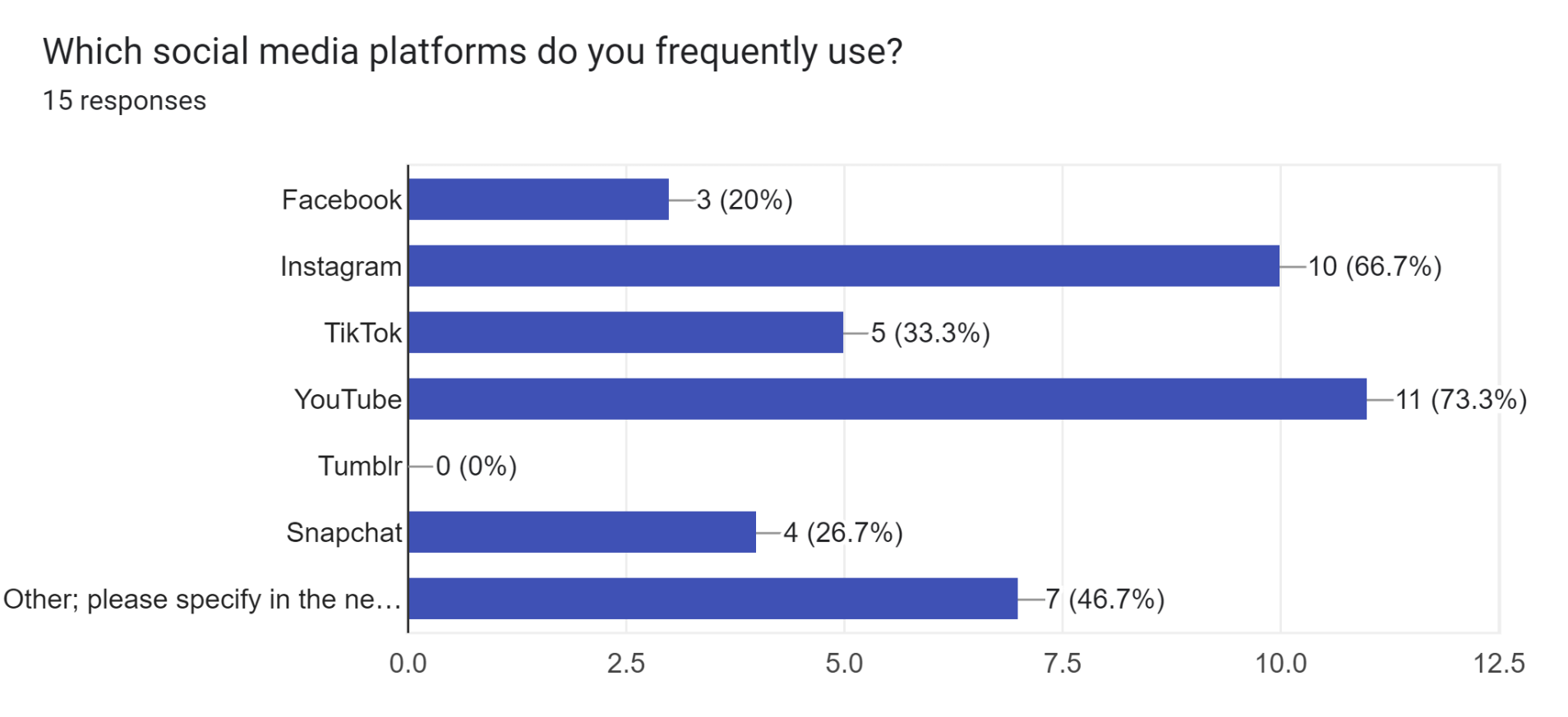

The most popular social media platforms were YouTube, Instagram, and Twitter. The survey allowed participants to write in any site they used if it wasn’t listed.

The reported hashtags on the participants’ feeds had two outliers; one stated seeing hashtags related to Donald Trump often, while another simply saw “politics” on their feed. Others tend to see posts containing dogs, cats, fashion, trends, or celebrities.

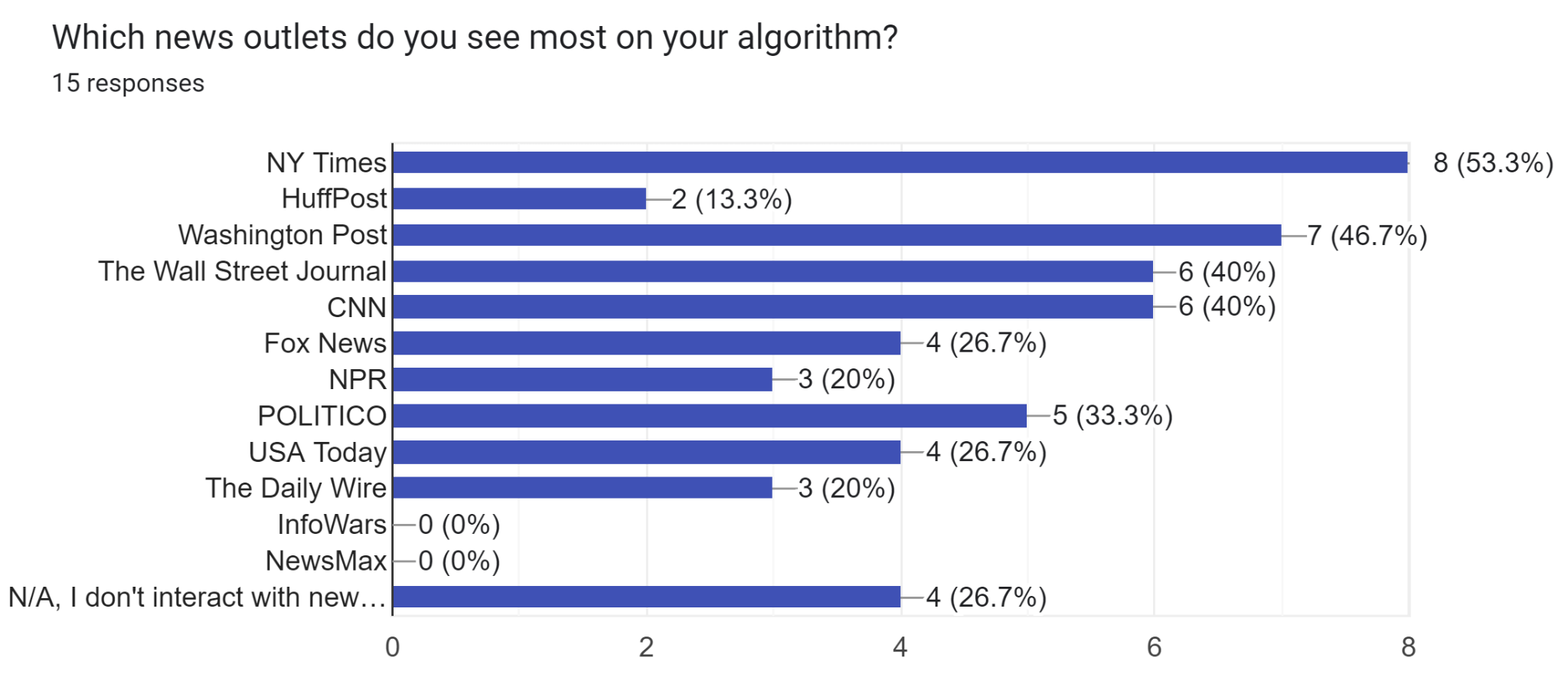

Despite only two people having political hashtags appear on their pages, eleven people self-reported interacting with at least one news outlet online. For this particular question, political affiliation was irrelevant as the algorithm’s perception of the users was in question.

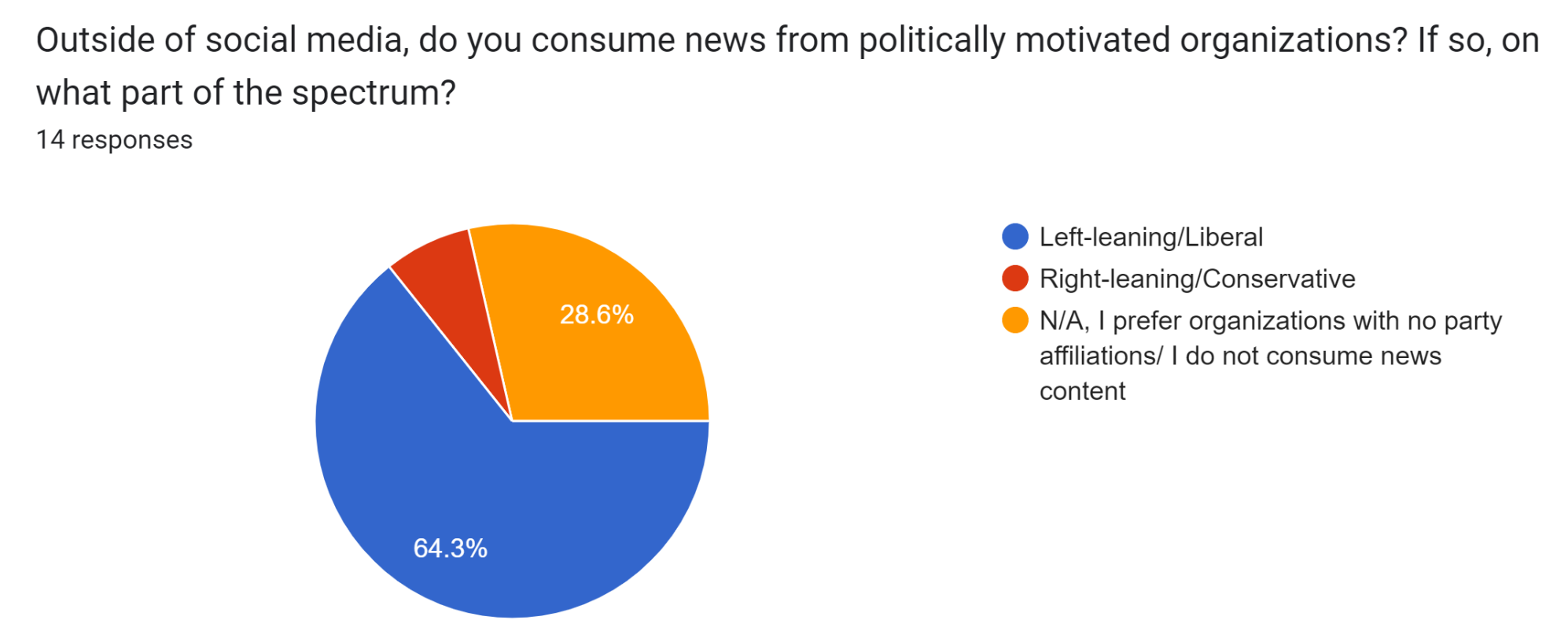

The next question asked if participants consume news from politically motivated organizations, and if they did, what part of the political spectrum it was on. One person declined to answer, but out of the fourteen left, 64% reported consuming Liberal-aligned media, yet 29% reported they did not consume politically motivated news outside social media. Only one person, or 7%, reported consuming Conservative-aligned news media.

Media and the Persuasion Effect

DellaVigna and Professor Kaplan’s research suggests media causes a persuasion effect. The voter turnout of a town they were monitoring shifted toward the Republican party after a period of having access to Fox News on their televisions.

They also found that having Fox News in general increased voter turnout. Since the channel covers mostly general politics functional for elections, the voter turnout for presidential elections was higher compared to senate races that were less popular with the outlet.

On a similar note, participants self-reported if they only interact with the content they politically align with, if they hear multiple perspectives on issues they care about, and why they take their specific position.

Once again, one participant left this question blank, but fourteen people still responded. Ten survey participants self-reported interactions with content outside their affiliation and content explaining different perspectives on one topic.

The common factor shared by all ten participants was following accounts and liking content made by the opposing side to even out their algorithm. Interestingly, none reported blocking out opposing content as they are still open to hearing other views, even if it’s just to disagree, which may not be the case with everyone.

Dr. Levy’s research supports the notion that a diverse algorithm lowers polarization. He explains, “…if the feed had an equal share of pro- and counter-attitudinal news, the difference between the feelings toward one’s party and the opposing party would decrease”. He also asserts the “diet” of one’s social media page depends on the content they interact with; the slightest change in behavior can drastically change the algorithm.

Algorithms like Facebook work hard to show users content they are prone to like but not necessarily new information. The online “diet” carefully considers the interests and dislikes of users to “feed” them attractive content.

Participant Demographics

Two participants chose to withhold certain demographic information, but every participant reported their generation. There was only one Millennial in the midst. All other participants reported being Gen-Z. Fourteen people identified as exclusively heterosexual- while one identified as generally queer.

The gender divide was more even with eight women and six men. Nine people identified as white, four as Asian, and one as African-American. Four people stated they were left-leaning, two were right-leaning, three were centrists, and two had no political affiliations.

Since we were anticipating a larger sample size, we were also expecting to make evidence-based connections between the demographic of participants and their online activity. Unfortunately, due to the sample size, we cannot accurately assume a relationship between factors other than political affiliation and online political activity.

Being Gen-Z and analyzing the data provided by our fellow Gen-Z participants, it wouldn’t be wrong to assume the outlook our age group has on political participation. As most participants stated, they feel their social media “diet” consists of ideologies they’re familiar with.

They also added they wouldn’t mind hearing from the opposing side. Although their feed’s typical content may influence them to view political topics a certain way, they’re still open-minded.

Is Social Media Controlling Us More Than We Thought?

The primary research’s outcome was congruent with Dr. Levy and DellaVigna’s work. Just as cable TV can affect voter turnout, social media news outlets have the same effect. Social media algorithms have become worse than cable when it comes to polarization. Algorithms are tailored to our interests and oppositions; they’ll tune out content they assume users won’t interact with to push confirmation bias and clickbait.

While the platforms should filter harsh and misinformed posts, they may accidentally favor one end of the spectrum. Increasing feelings of discrimination only separates the population further, feeding into polarization.

Being fed content you’re “guaranteed” to enjoy, of course, has its drawbacks. CBC News reporter Ramona Pringle’s article on content blindness discusses the tactics used by social media companies to divide voters. Our algorithms create an echo chamber of perfectly tailored content that further confirms our biases.

For example, Facebook prevents users from hearing much of the opposing side, making it incredibly easy to fall into a constant and false sense of agreement with one’s views. If the patterns of information in our minds remain undisturbed, we won’t feel the need to seek out a second opinion, a fresh perspective.

As supported by Dr. Levy’s findings, feelings of polarization decrease as bipartisan interaction increases. In the case of our analysts and journalists, it may just be a selfish algorithm holding you back from open-mindedness.

Despite having a short history, social media has controlled an entire election and divided the country. The effects are not surprising or new, but social media has proven to influence voter behavior more than traditional forms of media. The internet is more accessible than ever, but so is disinformation.

Is There Hope for Our Political Climate?

Although social media’s effects on politics have been insignificant in the history of government and political science, it’s catching up to more historically influential media forms like television. As DellaVigna and Kaplan explained, the media bias in small towns can wreck the political climate and keep voters from seeking opposing information.

Social media has the same effect, except it applies to a broader range of viewers and is even more accessible. With algorithms working hard to confirm our biases, we are in an awkward position to reject ideologies we don’t understand without giving them a chance.

Just as disinformation is always one click away, fact-checking resources are available. Google can search its entire database for any question within seconds. If you come across questionable news on social media or headlines that sound too good to be true, you can confirm the information cited by researching its source.

There is also software, our very own Biasly extension, that can do the same research for you. It checks the organization, the author, and the language used in the news article to ensure you’re reading valid content.

If you are willing to put the effort in, your social media “diet” won’t be able to gaslight you into keeping specific political beliefs. The main issue with social media, other than accessibility, is comfort. Users don’t need to switch between apps to receive their news if Facebook pushes it to them. If users are willing to pay the price of comfort, they can avoid political blindness and effectively participate in society.