For years, the debate around the College Football Playoff has revolved around one central question: how do we balance fairness, excitement, and revenue without destroying the regular season?

A well-designed 16-team playoff can do exactly that—and the proposal outlined here is one of the cleanest, most compelling blueprints yet.

Below is an argument for why the NCAA should take this model seriously, and why fans, players, and administrators all stand to benefit.

Our 16-Team College Football Playoff Proposal

In our version of the CFP with 16 teams, each of the four major conferences receives two automatic bids as detailed below, ensuring both competitive balance and meaningful conference play.

- One automatic bid goes to the conference champion, rewarding the team that wins its league on the field and preserving the importance of conference title games.

- The second automatic bid goes to the highest‑ranked team from that same conference in the CFP rankings before conference championship games, regardless of whether that team plays in the title game.

This structure recognizes both postseason performance and sustained excellence over the full season, blending the value of a late surge with the consistency of a strong year.

This approach keeps conference titles meaningful, but doesn’t let a fluky championship‑game upset destroy the season of an otherwise elite team. A powerhouse that stumbles in one game after months of dominance still has a path into the playoff, which feels fairer to players, coaches, and fans who understand how thin the margins can be in a single matchup. It also prevents one lucky break or one bad bounce from entirely distorting the national picture.

At the same time, it protects top teams that miss a championship game due to division structure, tiebreakers, or early‑season losses, reducing the impact of quirks in scheduling or conference alignment. By guaranteeing two automatic bids per major conference, it ensures every league is deeply invested in the playoff race, not just at the very top, but in the battle for that crucial second bid as well. That keeps more programs and fan bases engaged into November, raising the stakes for a wider range of games across the country.

At‑Large Bids: 8 Spots, Best Teams Available

After the eight automatic qualifiers are locked in, the field is rounded out with eight at‑large bids, preserving space for the very best teams regardless of conference affiliation. These spots go to the next eight highest-ranked teams in the CFP rankings before championship weekend, with no conference limits on at‑large selections. This approach keeps the playoff focused on quality, not politics, and allows the bracket to reflect the true strength of the season’s top programs.

- The playoff remains a best-teams tournament, not a quota system.

- If one conference is truly loaded in a given year, it can earn multiple at‑large spots.

- Strong independents and Group of 5 teams with elite seasons have a clear, objective path: get ranked high enough.

Seeding: Strictly by CFP Ranking

Once the 16 teams are selected, they are seeded 1 through 16 purely by CFP ranking, creating a straightforward and transparent bracket. Conference champions receive no special seeding advantage beyond where they already stand in the rankings; ranking alone determines their position. This avoids the confusion of preferential treatment and ensures that seeding reflects how a team’s full body of work is evaluated over the entire season.

That approach is simple, transparent, and fair, and it puts real pressure on the committee to get the rankings right, not just for the top four but throughout the field. It also avoids messy reseeding rules and protects bracket integrity, allowing fans and teams to clearly understand the path to the championship from the moment the bracket is revealed.

The Bracket: A True 16‑Team Knockout

The playoff unfolds as a true 16‑team knockout tournament, using a familiar and intuitive structure. First-round matchups follow a standard 16-team bracket (as seen below) with teams advancing through single elimination into the quarterfinals, then semifinals, and ultimately the national championship. This is the classic bracket format that fans already understand from basketball tournaments, the NFL playoffs, and high school postseason play across the country, making the path to the title both clear and compelling.

Single elimination → quarterfinals → semifinals → national championship. This is the format fans understand from basketball, the NFL, and high school playoffs across the country.

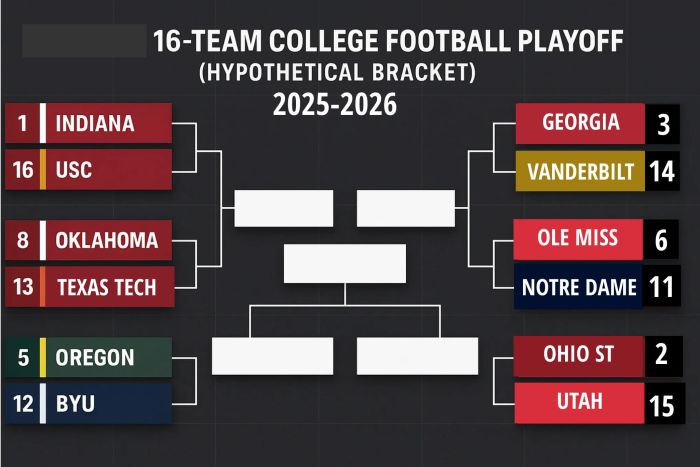

What a 16‑Team Bracket Actually Looks Like in 2026

Using a 16‑team bracket based on the final 2025–26 College Football Playoff rankings, the Round of 16 would look like this:

Left Side

- (1) Indiana vs (16) USC

- (8) Oklahoma vs (9) Alabama

- (4) Texas Tech vs (13) Texas

- (5) Oregon vs (12) BYU

Right Side

- (3) Georgia vs (14) Vanderbilt

- (6) Ole Miss vs (11) Notre Dame

- (2) Ohio State vs (15) Utah

- (7) Texas A&M vs (10) Miami

Bluebloods vs. upstarts

- Reborn power Indiana as the No. 1 seed facing a traditional heavyweight in an unfamiliar role as the underdog, USC

- SEC juggernaut Georgia taking on surprise conference climber Vanderbilt

Classic brand‑name clashes

- Oklahoma vs. Alabama is a made‑for‑TV playoff blockbuster

- Texas A&M vs. Miami matches two massive brands with national footprints and very different identities

Conference rivals on a neutral stage

- Texas Tech vs. Texas drops a bitter rivalry into a win‑or‑go‑home playoff setting instead of a random October Saturday

Cross‑regional / cross‑style matchups you rarely see in bowls

- Oregon vs. BYU pairs a Big Ten power with a physical Big 12 contender

- Ole Miss vs. Notre Dame brings together SEC tempo and an independent national brand with its own style and identity

This is exactly what the sport says it wants: big games, national matchups, and high stakes spread across the entire bracket, from 1 vs. 16 all the way to 8 vs. 9.

Why the NCAA Should Seriously Consider This Format

1. It Preserves—and Elevates—the Regular Season

One of the biggest criticisms of expansion is that it “devalues the regular season.” This format does the opposite.

Here’s how:

- Race for automatic bids: Every major conference has two guaranteed tickets on the line. That makes conference games in October and November more important, not less.

- Race for seeding: Going from a 6-seed to a 3-seed can change your path dramatically. Teams have a real incentive to finish strong, not coast once they’re “in range.”

- Race for at‑large spots: Dozens of teams are alive deep into November for the 8 at‑large bids. That keeps fan bases engaged and TV windows relevant longer.

Instead of narrowing the focus to 4 teams by mid-November, this system keeps 15–25 teams in serious contention late into the season.

2. It Delivers More Meaningful Games Without Diluting the Championship

The fear that “too many teams” will make the title less meaningful overlooks a key point: 16 teams does not mean 16 equal contenders. Expanding the field increases access and intrigue without suddenly turning every qualifier into a realistic favorite to win it all.

In reality, the top 4–6 teams will still be the primary championship favorites, just as they are now. Lower seeds become regional heroes and upset threats, capable of shaking up the bracket and creating memorable moments. The structure mirrors the NFL: plenty of playoff teams to deepen interest and opportunity, but still a relatively small group of true favorites at the top.

The early rounds deliver drama and upsets; the later rounds usually still deliver the best vs the best. That’s exactly what you want.

3. It Balances Power Conferences Without Artificial Limits

By giving each major conference two automatic bids and then going fully merit-based with the remaining eight spots, the system strikes a balance between guaranteed representation and competitive fairness. Every major league knows it will be present in the playoff field, but beyond that baseline, performance—not politics or protection—determines who gets in.

In practice, that means no conference is guaranteed more than two spots, but none is capped either. If a conference has a historically strong year, its teams can earn multiple at‑large bids based on their rankings and résumés. If another conference is down, it won’t be artificially propped up by soft rules, ensuring the bracket reflects the actual strength of the season rather than attempts to engineer parity.

This hits the sweet spot: conference representation is guaranteed—but not overprotected.

4. It Gives Players More Opportunities Without Endless Travel

A 16‑team playoff might sound like a lot, but consider:

- Only two teams play four games (semifinal winners).

- A large number of players already travel for non-playoff bowls that carry less meaning and lower stakes.

- With careful scheduling and regional site selection (especially in the Round of 16), the total load is manageable.

In exchange, players receive:

- More national exposure

- More NFL scouting opportunities

- More NIL money and opportunities

- The chance to compete for a true national championship, not just a bowl trophy

That’s a trade-off most players—and recruits—will gladly take.

5. It Dramatically Increases Revenue and Exposure

From the NCAA and network perspective, this format is a dream:

- 8 first-round games, each with playoff branding and stakes

- 4 quarterfinals

- 2 semifinals

- 1 national championship

You’re looking at a 13-game playoff inventory, all with high viewership potential.

Compare that to the current model with limited playoff games and a bunch of bowl games many fans only casually follow. A 16-team playoff concentrates the excitement, turning December and early January into a multi-week national event that consistently draws attention from across the country.

That means higher media-rights deals, stronger sponsorship opportunities, and more cross-country engagement and storylines, as every round delivers meaningful, nationally relevant matchups that fans have a reason to watch.

Competitive Fairness: More Teams, Less Controversy

A persistent problem with the 4-team model is the “who got left out?” narrative. A 16-team field doesn’t erase controversy, but it does move it down the ladder.

Instead of arguing: “Is Team #5 unfairly left out of a possible championship?”

You’re arguing: “Is Team #17 unfairly left out of the field?”

That’s a much less damaging controversy. No system is perfect, but this one dramatically reduces the chance that a legitimate title contender is excluded. At the same time, seeding by ranking avoids political maneuvers and complicated protections. If you’re better, you should be seeded higher. It’s that simple.

Reasons and Biases of Why it Might Not Happen

1. “The Old System Is Good as It Is” – Status Quo Bias & System Justification

When people insist that “the old system is good as it is,” they’re often not making a purely rational argument—they’re being pulled by a cluster of cognitive biases, especially status quo bias and system justification.

Status Quo Bias: Comfort With the Familiar

Status quo bias is the tendency to prefer the current situation simply because it’s current, not because it’s objectively better. It shows up as an instinctive comfort with what already exists and a reflexive skepticism toward anything new, regardless of how strong the case for change may be.

In college football terms, that looks like fans, media, and decision-makers saying, “We’ve always done it this way with a small playoff, the BCS, or polls—so it must be right.” Any proposed change is treated as inherently suspect, even when there is evidence that it could improve fairness, excitement, or revenue. The potential downsides of change get magnified and repeated, while the very real flaws in the current setup are minimized, normalized, or ignored.

People also tend to forget that the “old system” they are defending has already changed multiple times. College football has moved from polls deciding champions, to the BCS, to a 4-team College Football Playoff, and now to expanded formats being actively debated. What feels like tradition is often just the most recent version of change that people have gotten used to over time.

Every one of those transitions was once criticized as dangerous or unnecessary. Yet each new stage quickly became “the way it’s always been” in the minds of many fans and stakeholders.

System Justification: Defending an Unfair Setup

System justification is our tendency to rationalize existing rules and hierarchies, even when they disadvantage many participants.

- Fans and media justify the old system by saying “only the best 2–4 teams deserve a shot,” even when those teams are chosen via subjective rankings and limited data.

- They defend exclusion as a virtue: “If you didn’t make the top 4, you clearly weren’t good enough,” ignoring the reality that teams with similar résumés are treated very differently.

- They accept structural advantages (brand recognition, media markets, historical prestige) as “earned” rather than as part of an entrenched system.

This mindset glosses over:

- Teams locked out because of preseason perceptions.

- Conferences with fewer opportunities for big-stage validation.

- The way historical reputation shapes rankings and expectations.

The core bias: if a system exists, people assume it must be fundamentally legitimate, and they instinctively defend it against change—even if a new system could produce more accurate and equitable outcomes.

2. “The New System Will Harm College Football” – Loss Aversion, Negativity Bias & Nostalgia

The claim that “the new system will harm college football” often isn’t grounded in actual evidence from expanded playoffs or other sports. It’s usually a mix of loss aversion, negativity bias, and nostalgia bias.

Loss Aversion: Fear of Losing What Works

Loss aversion is the tendency to feel potential losses more intensely than potential gains. Psychologically, a possible setback looms larger than an equally sized benefit, which often makes people more cautious and resistant to change than the facts alone would justify.

In the context of college football playoff expansion, that means many people fear “ruining the regular season” more than they value the potential gains of more meaningful games for more teams, fewer arbitrary exclusions, and more regional and national matchups. The prospect of altering a familiar structure feels threatening, even if the new system could enhance competitiveness and engagement.

As a result, they overestimate what might be lost—mystique, exclusivity, tradition—and underestimate what might be gained, such as better representation, fairer outcomes, and new rivalries. Loss aversion tilts the conversation toward protecting what already exists instead of honestly weighing how much a broader playoff could improve the sport for a wider range of programs and fans.

Even when data from other sports (e.g., March Madness, NFL expansion, conference title games) suggests that expansion boosts overall interest, people focus on worst-case scenarios: “It will be all blowouts,” “Fans will stop caring,” “It’ll be too corporate,” etc.

Negativity Bias: Overweighting Worst-Case Scenarios

Negativity bias is our tendency to give more psychological weight to negative possibilities or events than to positive or neutral ones.

A single boring playoff game quickly becomes “proof” that expansion waters everything down, even though unexciting games already exist in smaller formats and regular bowls. One dull matchup is treated not as an outlier, but as a warning sign that the entire expanded system is flawed.

At the same time, hypothetical issues like player fatigue, scheduling confusion, and fan burnout are treated as inevitabilities rather than challenges that can be managed. Potential positives—such as underdog runs, conference validation, and increased national interest—are dismissed as unlikely or trivial, even though history in other sports shows that these benefits often define the appeal of larger playoff fields.

Instead of asking “what problems does the current system already cause?” critics fixate on imagined future problems while ignoring:

- Current controversies over who gets left out.

- Bowl games that already lack meaning for top programs.

- Fan bases who tune out by November because their teams have no realistic title path.

Nostalgia Bias: Romanticizing the Past

Nostalgia bias is the tendency to idealize earlier eras and assume they were better, simpler, or purer. It makes the past feel not just different, but inherently superior, even when the reality was far more complicated and flawed than memory suggests.

In college football, this looks like glorifying the old poll‑era or BCS era as more “authentic,” while forgetting the split national titles, champions crowned without ever playing each other, and blatant regional and brand favoritism that defined those systems. It also shows up in phrases like “we’re losing what made the sport special,” offered without acknowledging how much the sport has already evolved through massive TV deals, NIL, conference realignment, and soaring coaching salaries.

Nostalgia selectively edits out the downsides of those eras and frames any modern change—especially a bigger playoff—as a betrayal of tradition. Combined with other cognitive biases, it makes any new system feel dangerous by default, even when the proposed change is designed to fix long‑standing structural problems in how champions are decided and who gets a fair shot at the title.

3. Blueblood Bias – How Elite Programs’ Thinking Holds the Sport Back

The “bluebloods” of college football—traditional powerhouse programs with massive brands—often exhibit a distinct set of cognitive biases that shape their resistance to change. These biases don’t just protect their interests; they can hold back the evolution of the sport as a whole. Key biases at play: self-serving bias, survivorship bias, and halo effect.

Self-Serving Bias: Protecting Their Advantage

Self-serving bias is the tendency to interpret systems in ways that benefit ourselves and to justify those benefits as “earned” or “deserved.” It shapes how people see fairness, success, and merit, often blurring the line between genuine achievement and structural advantage.

For blueblood programs, that looks like preferring smaller playoffs or subjective selection processes that privilege reputation and the “eye test” over on-field résumés. It includes arguing that “only a few elite teams can truly win it all,” which conveniently aligns with the same handful of traditional powers. It also means framing their consistent inclusion in national conversations as proof that the system works, rather than as evidence that the system is tilted toward known brands.

When an expanded playoff is proposed, their objections often sound philosophical (“we must protect the regular season”) but are actually practical: more teams = more competition = more chances to be upset or exposed.

Survivorship Bias: Mistaking Their Story for the Whole Story

Survivorship bias happens when we focus on the “winners” and ignore the many others who had similar ability but never got the same opportunities.

Blueblood thinking often says:

- “We climbed to the top under the old rules, so the rules must be fair.”

- “If other programs were good enough, they’d break through too.”

This ignores:

- Historical head starts (money, facilities, media coverage, recruiting pipelines).

- Barriers for smaller or emerging programs (limited access to marquee games, weaker conference perception, less preseason hype).

- How often borderline playoff calls go to name-brand teams instead of equally deserving upstarts.

By focusing on their own success as evidence that the system works, bluebloods downplay how many quality programs never get a fair shot to prove themselves on a big stage.

Halo Effect: Branding as a Substitute for Merit

The halo effect is when one positive attribute (history, brand, iconic coaches) causes us to overrate a team in other areas (current performance, relative strength).

With bluebloods, voters and media often give the benefit of the doubt to traditional powers in preseason and early polls. Close calls in rankings tend to favor the helmet logo rather than the actual résumé, and a two-loss blueblood is frequently treated differently than a two-loss newcomer, even when their schedules and results are very similar.

Blueblood programs often unconsciously defend this by saying, “We play tougher schedules,” “We recruit better,” or “We’ve proven it over time.” Some of that is true—but it becomes circular. They get more exposure, which leads to better recruits, which strengthens perception, which results in more favorable rankings, which then leads to more playoff access and even more exposure, and so the cycle continues.

This halo effect distorts competitive balance and makes it harder for the sport to evolve into a more merit-based system where performance, not just prestige, determines opportunity.

How Blueblood Bias Holds the Sport Back

When these biases combine, the result is resistance to reforms—like a robust 16‑team playoff—that would reduce the advantage of historical reputation, give emerging programs a realistic route to the national stage, and expose bluebloods to more high‑stakes matchups against well‑prepared challengers. The very changes that would open doors for more teams are perceived as existential threats by those who have long benefited from a narrower, more exclusive system. Instead of evaluating the proposal on its merits, people often evaluate it based on how much it disrupts the familiar hierarchy.

From the perspective of the sport as a whole, expanded, fairer playoffs would mean more fan bases feeling empowered and engaged, broader national relevance, and a more honest reflection of who is actually best on the field. A wider bracket pulls more regions, conferences, and programs into the national conversation deep into the season, turning late‑season games into stepping stones rather than dead ends. It also aligns results more closely with on‑field performance instead of preseason hype or brand perception.

From the perspective of entrenched powers, that’s scary—and cognitive biases give them a ready‑made mental toolkit to argue that what’s best for them is what’s best for college football. By framing expansion as harmful to tradition, the regular season, or the purity of the sport, they can mask self‑interest as guardianship. In reality, acknowledging these biases is the first step toward recognizing that a more open, competitive playoff system strengthens the game for everyone, not just the schools that have dominated under the old rules.

But once you recognize:

- status quo bias in defending the old system

- loss aversion and nostalgia in fearing new formats

- and self-serving, survivorship, and halo effects in blueblood resistance

It becomes easier to see that many objections to a more inclusive playoff system are not purely about “protecting the sport.” They’re often about protecting an existing hierarchy.

And that hierarchy is exactly what a well-designed, 16-team playoff aims to challenge—on the field, where it should be decided.

Addressing Common Concerns

1. “Won’t blowouts ruin the early rounds?”

Occasional blowouts already occur in the 4‑team format and in New Year’s Six bowls, so lopsided scores are not unique to an expanded playoff. The difference in a 16‑team system is that upsets become more plausible with a broader field, and even mismatched games carry real national importance because every matchup is part of a survive‑and‑advance path to the title. A lower seed knocking off a giant becomes more than a quirky bowl story—it’s a true playoff upset with clear consequences for the bracket.

College basketball offers a clear parallel: it has its share of lopsided 1 vs 16 games, yet March Madness remains one of the most beloved events in sports. Fans don’t show up only for evenly matched contests; they show up for the stakes, the upsets, and the possibility that someone shocks the world. A 16‑team college football playoff would tap into that same drama, turning even potential blowouts into must‑watch events because of what’s at stake.

Fans tune in because of the stakes, the upsets, and the possibility that someone shocks the world.

2. “Doesn’t this make the committee too powerful?”

This model actually clarifies the committee’s role:

- They set the CFP rankings.

- Those rankings determine everything: bids, at‑large selections, and seeding.

- There are no extra layers of subjective rules (e.g., protecting conference champs in seeding).

The process becomes: rank the teams properly, let the bracket speak.

The Big Picture: A Better Version of College Football

The proposed 16-team playoff doesn’t just add more teams; it repairs three long-standing structural issues:

- It reduces the disproportionate power of preseason perception and early-season losses.

- It keeps more fan bases alive and engaged throughout the year.

- It creates a clear, fair, and exciting path to the national championship.

Most importantly, it aligns with what college football already is at its best – regional passion, national reach, and high-stakes games that everyone wants to see.

For the NCAA, adopting a 16-team playoff with this blend of automatic bids, at‑large spots, and ranking-based seeding is not just about more games—it’s about elevating the entire sport.

This is not expansion for expansion’s sake.

It’s evolution—toward a playoff that truly reflects the depth, diversity, and drama of college football.